A cautionary tale: Movies for the influencer era.

By Darragh Leen

Most shifts in societal norms over the decades have gone hand in hand with storytelling for the silver screen. The hippie movement of the late 1960’s saw a string of free-spirited films released into theatres all over the world. Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider introduced cinemagoers to the freedom of not wholly attaching oneself to the regulations of society, breaking free and exploring untouched avenues, whether by way of a Harley-Davidson or not. It told the public that it was ok to let go. The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine and The Monkees’ Head also celebrated the movement, painting it in a positive light. J. Hoberman’s essay on the 1969 classic digests it perfectly by saying:

“Easy Rider presented itself as a generational statement… [it] revelled in countercultural values…”.

That said, Hopper’s revolutionary exploitation trip was only one of a finite number of pictures that purportedly glorified the hippy lifestyle. There was a category of films in the same vein that took a different stance on the idea of the counterculture. These films acted as cautionary tales, perhaps from those that had already experienced the horrors that became the movement. Exaggerated films in the vein of The Acid Eaters, Cisco Pike and Jigsaw (plus a bunch of tacky Manson-inspired flicks post-Tate/La Bianca murders) tried to ram the idea down the audiences throat that acid is bad, bad, bad and any sort of interaction with psychedelics would lead to criminal activity…maybe even murder.

Fast forward fifty years and swap out flower power for cancel culture, love-ins for lip-sync videos and live gigs for livestreaming. To call the ‘Influencer era’ a counter-culture movement would be a bridge too far, but it is safe to say that it is making similar waves to that of those in the late sixties. With the emergence of TikTok and the evolution of Instagram, platforms for people to showcase and promote themselves are becoming easier by the minute. Where society stands on these ‘influencers’ is still up for debate. It goes without saying, however, that the generational gap plays a part in how this side of culture is viewed.

In reality, those born before the turn of the century will look down on these people as narcissistic opportunists with nothing but a vapid desire to go ‘viral’ or hit a certain number of followers. The so-called Gen-Z folk are willing to accept this as natural evolution, the way society was always destined to go, and they want in. Where do the filmmakers of Mainstream, Eighth Grade, Sweat, Ingrid Goes West and Spree stand on these issues, though? That is the question.

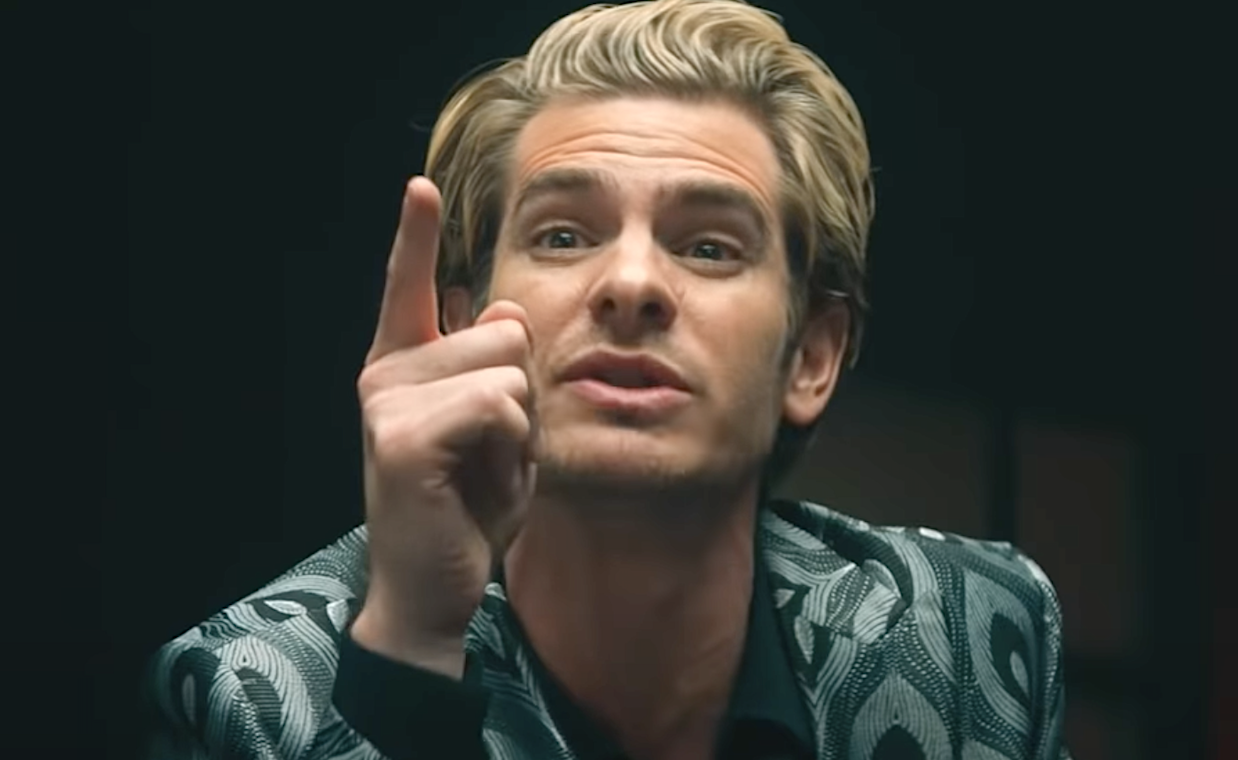

The approach Gia Coppola took to Mainstream was very much along the lines of an updated version of the 1957 flick A Face in The Crowd, which starred Andy Griffith as a lowly folk singer elevated to stardom after appearing on national television. Once Griffith’s protagonist Rhoades experiences the highs of fame his sinister ego bubbles to the surface. This is mirrored by Andrew Garfield’s character Link in Mainstream. He may conclude his arc as ‘No One Special’ – the influencer and internet personality the world wants to meet - but Garfield’s social media sensation begins as nothing but a sign twirling eccentric, dressed in a mouse costume, clambering for change.

The rise of both characters to unspeakable fame (or notoriety) is jarring, but these montage-like progressions give us a clearer picture on who these men used to be and who they are now as a product of celebrity. The theatrical release poster for Elia Kazan’s Face in the Crowd read:

‘Power! He loved it! He took it raw in big gulpfuls…he liked the taste, the way it mixed with the bourbon and the sin in his blood!’

It is prominence, and only prominence, that turns Link onto the idea that the platform he is being showcased on isn’t all that bad. He initially believes that such platforms are the scourge of society – perhaps mirroring Coppola’s own feelings on the issue. The director brings the moral tale to the audience and doesn’t show any intention of hiding her feelings on the characters she has created. In a nutshell, what Coppola is trying to tell us is that the platforms themselves are not to be held accountable but the narcissists who paste themselves all over TikTok are.

Does the idea of popularity change the make up of the person or has the egomaniacal fame-hungry sociopath always been there waiting to get out? This is another question posed by not only Coppola but Eugene Kotlyarenko, director of Spree, and Matt Spicer, director of Ingrid Goes West.

Spree (oddly enough, produced by none other than Champagne Papi himself, Drake) is an interesting case. A perfect addition to the ‘person not the platform’ argument, Spree was dubbed by Collider as “American Psycho for the digital age”. We’re starting to notice a trend here. Movies about Megalomaniacs and the effect that social media has on their lives. To pose another question, how many influencers do we think just want to be seen and how many do we feel are actual bona fide Megalomaniacs?

You might feel the word is hyperbole at its finest, but it’s worth thinking about. These films certainly get you thinking about just that and that is exactly what the filmmakers want. We know which side they are on by simply reading the plot synopsis. Kotlyarenko’s comedy-horror sees Kurt, a wannabe live-stream star, go to extreme measures to attain follower goals. Kurt places spiked water bottles in the back seat pockets, runs over his passengers, and stalks those that he admires. All this for the chance of a moment in the spotlight.

We’re placed in similar territory in Ingrid Goes West, which stars a suitably unhinged Aubrey Plaza as the titular character. Our protagonist moves out to Los Angeles to meet her idol, a popular social media influencer named Taylor Sloane. The poster tagline smartly reads ‘She’ll follow you’. Spicer doesn’t waste any time in showing his audience the dark side of our protagonist. In the opening scene Ingrid pepper sprays an influencer who (understandably) doesn’t respond to her incessant messaging. Spoiler alert: Things don’t get any easier for Ingrid after this. She carries out the same methods with Sloane, with limited success, only this time she does meet her ‘idol’.

What begins as friendly encounters and even being invited to the Taylor’s house for dinner with her and her husband slowly turns to uncomfortable scenarios between the two and eventually a dramatic breakdown of the relationship (was it ever really a relationship?).

Spicer’s study on the influencer’s influence (for better or for worse) tends to look at the other side. The side of the influenced not the influencer. Meanwhile Bo Burnham’s Eighth Grade seems to straddle the line. Kayla, an angst-ridden teen who simply wants to hide in the shadows, has the secret desire to be popular. By day she cowers away from social interaction, by night she quietly conducts self-help tutorials in her bedroom hoping even one person will notice her.

Kayla is certainly influenced but does she have the gall and strength of character to deal with the rejection of being a so-so influencer who nobody cares to give any time? It’s the idea that popularity and notability will somehow change her life for the better that seems to get Kayla up in the morning. Whether this is healthy or not is up for debate. Burnham’s portrayal of the social media influence is potentially the most realistic of all portrayals seen on the list given. The approach taken is that of one not picking sides. Burnham strikes me as the type to observe and not involve himself too heavily in one side of the argument and Eighth Grade is an example of his neutrality.

He sees social media as something to be wary of while also acknowledging the fact that it can be used for good. This doesn’t take from the fact, however, that her single father struggles to tear her attention away from the screen at any given moment, a common plight among any parent, albeit a problem which pales in comparison to the idea of murdering innocent people for followers a la Spree.

Sweat is perhaps the film that delves the deepest into the topic. Sylwia, an online fitness guru, is forced to confront her deepest insecurities when she hits the influencer jackpot. Here we are given another example of less hyperbolic examinations of the joys and subsequent perils of social media. Sweat’s Director Magnus von Horn and Bo Burnham both inspect the reality of the issue and don’t hold any punches in doing so. It’s brutal honesty from the two filmmakers.

Burnham is a lot more optimistic than his sceptical peers. In the words of Alyssa Bereznak of The Ringer , he portrays them as:

“outlets for self-expression. A place where they can find a voice, an audience and a community all their own.”

The bottom line is that all these films mentioned have something in common. They show us characters that are willing to do at least something outside of the norm, and at the most something extreme, to reach a higher level. Whether that be a higher level of consciousness, a higher level of popularity or a higher level in society. They show us the darkest desires of humans and what we are willing to do for just a little more.